Indefinite Detention of ‘Juvenile’ Offenders

HAYAT is shocked by the Parliamentary Reply on juvenile offenders detained under Section 97(2) of the Child Act 2001.

Section 97 of the Child Act 2001 provides imprisonment in place of the death penalty for juvenile offenders. It is also commonly known to many as “Tahanan Limpah Sultan” or TLS. Any juvenile detained as a TLS can only be released when a Board of Visiting Justices reviews their cases annually and provides recommendations to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, the Sultan of the State in question, or a governor for their release. In the past, this had resulted in cases where juvenile offenders were detained indefinitely and spent upwards of two decades in prison, if not more.

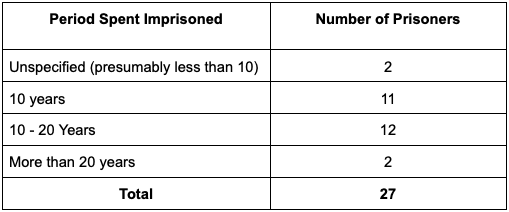

The Parliamentary Reply, published on 6 March, indicates the following:

The numbers are shocking, to say the least, as these are all juvenile offenders who were under 18 at the point of their offence. They are children who ought to have received due protection and rehabilitation as opposed to indefinite detention. Those who have spent more than 20 years indefinitely detained have spent their whole adulthood in prison and are now likely to have exceeded 40 years of age.

Section 97 is a relic from the times when Malaysia had the mandatory death penalty. The abolition of the mandatory death penalty and the resentencing process should have included the review for all 27 cases mentioned. From HAYAT’s observation of the resentencing process, they have all been explicitly excluded from the review process despite being sentenced under the mandatory death penalty regime.

There is no justification for any of these juvenile offenders to be detained indefinitely, and their detention should have been considered unconstitutional. Their continued detention represents the failure of the Malaysian government to uphold the rights of the children in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child given force through the Child Act 2001. This matter was brought to the government's attention as early as 2019, and successive administrations have failed to redress this flaw in our legal system.